The Concrete River by Luis Rodriguez:

The Concrete River by Luis Rodriguez:We sink into the dust,

Baba and me,

Beneath brush of prickly leaves;

Ivy strangling trees--singing

Our last rites of locura.

Homeboys. Worshipping God-fumes

Out of spray cans.

Our backs press up against

A corrugated steel fence

Along the dried banks

Of a concrete river.

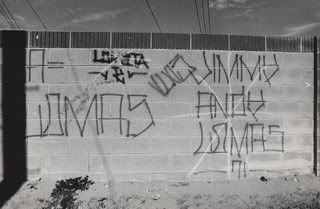

Spray-painted outpourings

On walls offer a chaos

Of color for the eyes.

Home for now. Hidden in weeds.

Furnished with stained mattresses

And plastic milk crates.

Wood planks thrust into

thick branches

serve as roof.

The door is a torn cloth curtain

(knock before entering).

Home for now, sandwiched

In between the maddening days.

We aim spray into paper bags.

Suckle them. Take deep breaths.

An echo of steel-sounds grates the sky.

Home for now. Along an urban-spawned

Stream of muck, we gargle in

The technicolor synthesized madness.

This river, this concrete river,

Becomes a steaming, bubbling

Snake of water, pouring over

Nightmares of wakefulness;

Pouring out a rush of birds;

A flow of clear liquid

On a cloudless day.

Not like the black oil stains we lie in,

Not like the factory air engulfing us;

Not this plastic death in a can.

Sun rays dance on the surface.

Gray fish fidget below the sheen.

And us looking like Huckleberry Finns/

Tom Sawyers, with stick fishing poles,

As dew drips off low branches

As if it were earth's breast milk.

Oh, we should be novas of our born days.

We should be scraping wet dirt

with callused toes.

We should be flowering petals

playing ball.

Soon water/fish/dew wane into

A pulsating whiteness.

I enter a tunnel of circles,

Swimming to a glare of lights.

Family and friends beckon me.

I want to be there,

In perpetual dreaming;

In the din of exquisite screams.

I want to know this mother-comfort

Surging through me.

I am a sliver of blazing ember

entering a womb of brightness.

I am a hovering spectre shedding

scarred flesh.

I am a clown sneaking out of a painted

mouth in the sky.

I am your son, amá, seeking

the security of shadows,

fleeing weary eyes

bursting brown behind

a sewing machine.

I am your brother, the one you

threw off rooftops, tore into

with rage--the one you visited,

a rag of a boy, lying

in a hospital bed, ruptured.

I am friend of books, prey of cops,

lover of the barrio women

selling hamburgers and tacos

at the P&G Burger Stand.

I welcome this heavy shroud.

I want to be buried in it--

To be sculptured marble

In craftier hands.

Soon an electrified hum sinks teeth

Into brain--then claws

Surround me, pull at me,

Back to the dust, to the concrete river.

Let me go!--to stay entangled

In this mesh of barbed serenity!

But over me is a face,

Mouth breathing back life.

I feel the gush of air,

The pebbles and debris beneath me.

"Give me the bag, man," I slur.

"No way! You died, man," Baba said.

"You stopped breathing and died."

"I have to go back!...you don't

understand..."

I try to get up, to reach the sky.

Oh, for the lights--for this whore

of a Sun,

To blind me. To entice me to burn.

Come back! Let me swing in delight

To the haunting knell,

To pierce colors of virgin skies.

Not here, along a concrete river,

But there--licked by tongues of flame!

Analysis:Rodriguez is particularly passionate about gang prevention and using the arts as an outlet for youth instead of violence on the streets. His first novel,

Always Running, actually started out as a letter to his son, in which Rodriguez details his own past gang involvement and the destructive path it led to. While it didn’t stop his son from being sentenced to prison, it has become an inspirational read for many Mexican-American youths today. Similarly, this theme reoccurs throughout Rodriguez’s poetry.

The title poem of Rodriguez’s second book of poetry,

The Concrete River, is a prime example of a poem that exhibits several reoccurring themes in Luis Rodriguez’s works. The title alone is an example of the theme of paradoxical descriptions in Rodriguez’s poetry. The word “concrete” gives the reader a sense of something that is fixed, unchanging, solid, man-made, and cold, while the word “river” has the feel of something that flows, is constantly changing, and natural. The combination of these two words as the title sets up a paradox description of what the narrator depicts in the poem.

The first section of the poem opens with the narrator, a young boy, and his friend as they hide in a make-shift shelter right off the streets of a city. The boys have their “backs press[ed] up against a corrugated steel fence along the dried banks of a concrete river” (Rodriguez). The streets are described as the river, and the “dried banks” denote the barren quality of life on the streets. There is no water, and there is no life. As the boys inhale spray-can fumes, the streets change: “This river, this concrete river, becomes a steaming, bubbling snake of water, pour over nightmares of wakefulness; pouring out a rush of birds; a flow of clear liquid on a cloudless day” (Rodriguez). With the use of drugs, the narrator can find an escape and can reach that place where there is an image of life depicted in the symbol of water. These images are the narrator’s aspirations of freedom from his current life, from “the black oil stains we lie in” (Rodriguez). In the visions induced from the drugs, the narrator says that him and his friend “[look] like Huckleberry Finns/ Tom Sawyers, with stick fishing poles, as dew drips off low branches as if it were earth’s break milk” (Rodriguez). Through drugs, the narrator returns to a natural state of lifestyle through the images of nature and fishing. It is definitely a more care-free way of living that the narrator pines for: “We should be scraping wet dirt with callused toes. We should be flowering petals, playing ball” (Rodriguez). The image of callused toes in wet dirt gives the reader an impression of rural life away from urban industrialization - a place where one wouldn’t even need shoes.

The paradox in the narrator’s visions lies in the narrator’s desires for the images to become a reality and the method through which he attains them. He longs for a world/lifestyle away from the man-made and industrialized, but he uses “technicolor synthesized madness” (Rodriguez) -- the drug -- to achieve the visions of nature. He inhales “this plastic death in a can” (Rodriguez) to see life.

At a turning point in the poem, the narrator’s visions change as his breathing stops (which is stated at the end of the poem). He enters “a tunnel of circles... Family and friends beckon me. I want to be there, in perpetual dreaming; in the din of exquisite screams” (Rodriguez). It seems as though the boy can see an afterlife where his friends and family are, but the descriptions of this place are, once again, very paradoxical in nature. He describes it as “perpetual dreaming” (Rodriguez), which would seem immensely attractive to the narrator who longs for escape from the world. At the same time, he calls it “the din of exquisite screams” (Rodriguez), which would imply something very attractive on the surface, but by using the word “screams,” he depicts something much harsher in reality. Rodriguez could be referring to the attractive nature of death or even to a harsher reality of hell.

The next section of the poem is very different from the rest of the progression so far. Its images are deep symbology of the narrator’s different stages of life. Through this symbology, the narrator revisits the progression of his life, similar to the flashbacks a person is said to have before death. At first the narrator is “entering a womb of brightness” (Rodriguez) which refers to pregnancy, then he is “a hovering spectre shedding scarred flesh” (Rodriguez) which describes birth and the departure from the mother’s flesh. The next stage refers to the narrator’s early childhood as a son who addresses his mother, “ama.” The boy, in this section, “flee[s] weary eyes bursting brown behind a sewing machine” (Rodriguez), which hints at the early stage of life where a child is kept with his mother while she works. The next stage of life Rodriguez refers to is when the narrator is a “brother, the one you threw off rooftops, tore into with rage” (Rodriguez). This signifies the time in the narrator’s life when he has both friends and enemies, possibly from being in a gang, and could have been betrayed by one of them. Rodriguez’s own history surfaces in the narrator’s voice at this point (Rodriguez was in a gang by age 11). The last part symbolizes the most recent stage of the narrator’s life as a “friend of books, prey of cops, love of the barrio women selling hamburgers and tacos at the P&G Burger Stand” (Rodriguez). Through these flashbacks, Rodriguez universalizes the narrator’s identity. The narrator tells the reader, “I am your son... I am your brother...” (Rodriguez). Through the use of word choice here, the character becomes someone close to the reader and more universalized.

As the boy sinks into death, he states “I welcome this heavy shroud. I want to be buried in it--” (Rodriguez). The narrator accepts death and the afterlife -- whatever that may be -- as a better option than his current life on the streets.

But before he can sink fully into the afterlife, he is pulled back to consciousness, “Back to the dust, to the concrete river” (Rodriguez). By using the word dust, Rodriguez emphasizes not only being brought back to life (through a Biblical context), but also to a dirtier existence, epitomized by life on the streets.

Once the boy regains consciousness, he longs desperately to return to his drug-induced visions: “Let me go! -- to stay entangled in this mesh of barbed serenity!” (Rodriguez). Here the narrator recognizes the danger in the pacifying images he creates through drug use. The description hints that the deeper he becomes entangled in the visions, the tighter barbed mesh will close around him. The image one can gather is of pleasure in suffocation. Even when his friend tells him “You stopped breathing and died” (Rodriguez), the narrator refuses to listen and keeps demanding for the bag with the spray can. The desperate desire for escape from life on the streets is extremely masochistic and paradoxical in its portrayal.

In the last section of the poem, the narrator comes down from his high and attempts to cope with reality. He tries “to reach the sky. Oh for the lights -- for this whore of a Sun, to blind me. To entice me to burn” (Rodriguez). In his surroundings, the only aspect of nature without the progress of industrialization is the sky. But even if he were to lavish in it, he would be burned by the sun. This metaphor symbolizes the little bit of futile hope left in the narrator’s life. He believes that even if he were to keep living, there would not be any point to do so. He longs to be “not here, along a concrete river, but there -- licked by tongues of flame!” (Rodriguez). The poem finishes on a frightening note. Whereas the earlier references to the afterlife were more vague, here the reference is pointedly about a hellish place. This interpretation takes the earlier symbols of escape to a completely new level. The narrator’s present situation, epitomized by the dry, the barren, and the lifeless, is so horrendous that even hell would be a more preferable place.

The overarching themes of homelessness, life on the streets, and drug use draw strongly from Rodriguez’s own background and lends much to his description of life in

The Concrete River. Rodriguez started using drugs at the age of twelve and was kicked out of his home by his parents for a while before coming back to live in his family’s garage. During that period, he was homeless and living off of the streets like the boy in

The Concrete River. Like his other works, this poem serves as a warning about the hopelessness of life on the streets. Frequently in the poem, the narrator calls the make-shift living area him and his friend inhabit “home for now” (Rodriguez). The repetition of this phrase demonstrates the impermanent lifestyle of the boys’ homelessness and the lack of a firm foundation to center their lives upon. When the narrator describes the door made out of a torn cloth, he adds in parentheses “(knock before entering)” (Rodriguez) in a disheartening attempt at humor. The description of the makeshift home imparts how much the characters attempt to make it a home, even though it is so impermanent and could never replace a real home.

Rodriguez also draws on his own experiences of drug addiction to depict the situations in his works. Drug use is a central theme in

The Concrete River, since it offers the only means of escape from this bleak life. But the effect of the drugs is either too temporary (they wear off too quickly) or too permanent (death). As the narrator in

The Concrete River almost faces his death, the reader can get a sense of the grim prospects so many boys like the narrator face everyday. When your only outlet can kill you, you must walk a fine line between death and living without hope.